Bonobo – An Expedition Diary by Andrew McAulay (Part I)

Introduction:

Bonobos are great apes whose DNA is more than 98% identical to that ofhumankind. They are only found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and are highly endangered due to hunting, logging and other pressures. In September 2013 Andrew McAulay visited DRC to learn about initiatives to protect bonobos and their habitats. By reading his expedition diary, below, we can experience his journey across various landscapes in search of wild bonobos and an intimate connection with nature.

Map of Africa. DRC is located in the heart of Africa (circled in red). (Image source: Google)

1.

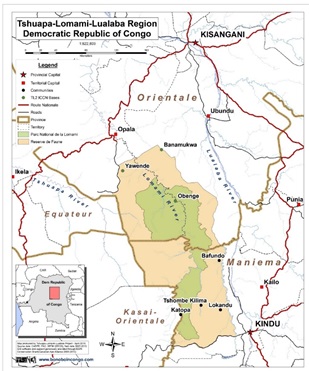

It is 5am, it is pitch black and I am drenched in sweat, picking my way through dense rainforest underbrush. I am with a small team of nature enthusiasts and researchers, searching for an elusive group of 23 bonobos in the remote Tshuapa Lomami Lualaba (TL2) region, named after 3 rivers, in the heart of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Even by the light of our head torches, the recently cut path is barely discernible.

Two hours later, we come to a halt; dawn is rising and some of us turn off our torches. According to the GPS reading, taken the previous evening as the bonobos were preparing their night nests, they should be about 700 meters to the right, off the “path”. We split into two smaller groups of 5; fingers on lips, no more talking… and as we close in on our target, I find myself choking with emotion. I should have known this would happen.

Suddenly, hands are pointing toward the distant canopy. I try to follow with my eyes… and I catch a glimpse: first of branches swaying and then of a distant swinging silhouette. Urgent whispers are directed toward Slo, bearer of the enormous camera lens that has won him the status of designated team photographer. He is hustled to the front, where he crouches, steadies his lens and captures the perfect shot: an adult bonobo, perched in his nest in the tallest of trees, alert but calm. The great ape gazes directly at us for a while, then disappears from view – and we can see by the movement in the trees that he is descending to the forest floor. The group have decided to move on – and the chances of us being able to follow are slim; but our mission is accomplished and our hearts are happy.

Everything has led up to this moment. Our week’s journey – by commercial airline, charter plane, four wheel drive, motorcycle, pirogue (dugout canoe) and finally foot - feels like a wave that has reached a high point on shore – and now it is time to retrace our steps.

A wild bonobo spotted in the forest. (Photo credit: Slobodan Randjelović)

2.

Bonobos are similar to, but distinct from, chimpanzees; with their smaller, less protruding jaw and brow-ridge, they are often referred to as humankind’s closest living relatives. Found only in the DRC, historically separated from chimpanzees by the great curve that is the Congo river, bonobos are listed as Category 1 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Population estimates vary from a few thousand to a few tens of thousand – and TL2 is one of 4 main areas where they still exist.

The TL2 “project” was established 7 years ago by Terese and John Hart, from the USA, who have been conducting research in the Congo since the early ‘70s. Their romance with the Congo has included a ground-breaking study of okapi (another unique and endemic DRC species, with the markings of a zebra, the neck of a giraffe and the head of an antelope) and spending 3 years living with Pygmies. Drawn by the endemic biodiversity and ecological intactness of TL2, the Harts have set up a programme of research and been instrumental in developing a proposal for the 9,000 square kilometer Lomami National Park. They have won the support of local communities and provincial governors and it is hoped that the State government will sign off soon.

As important as the Park are plans for a surrounding buffer zone “Reserve”, that would enlarge the total area of focus to 22,000 square kilometers (22 “Hong Kongs”, by the unit of measurement that I have become accustomed to). Around eighty villages exist in the proposed Reserve and their trajectory of development will be crucial to the protection of the Park. As in most of DRC, these communities are without electricity, schools, health clinics or any other modern infrastructure. Arguably - in some traditional, indigenous contexts - such services are not essential to wellbeing, yet DRC is a country that has been ravaged by war and unrest almost continually since independence from Belgium in 1960 (colonial occupation was also brutal and the days of King Leopold’s Congo Free State unspeakably so – in fact, it was so savage, that the human population was reduced by half); waves of migration have created a diverse ethnic mix, social cohesion has worn thin, corruption is rampant and the population is increasing. The easiest source of income is from the bush meat trade and these remote villages are convenient refuges for gangs of poachers.

There are plans for establishing community-managed forests within the Reserve – and ultimately, for eco-tourism. It is hoped that through the introduction of a combination of improved sustainable livelihood techniques and opportunities for income generation from Park management, the biodiversity will become an increasing source of sustenance and pride for local communities, thereby ensuring the sustainability of conservation initiatives. Yet there is a long way to go. People are restless and the Catholic Church has a strong presence in DRC; without education and effective family planning, women are vulnerable to exploitation and the number of humans will continue to rise.

Funding and other material support for the TL2 project comes from only a handful of international funders and NGOs. One of the most promising initiatives for the development of the Reserve is a partnership with the International Conservation Education Fund (INCEF). This NGO films and facilitates traditional community processes for identifying the most pressing challenges and seeking appropriate solutions; in this way they have created a vehicle for sharing experiences amongst rural participants and empowering them in the process. It is clear to villagers that the film content is authentic, for they themselves are the stars! Yet there might also be interviews with remote officials, responding to questions and concerns arising from the community discussions. Careful application of this approach in the TL2 context could provide a solid basis for helping people to relate to conservation goals and developing supportive community-based initiatives.

Map of TL2, DRC (Image source: www.bonoboincongo.com)

3.

One of the most well-established funders of bonobo conservation – and ape welfare in general – is the Arcus Foundation. Seeing the need for greater coordination amongst Great Ape funders, it has created a forum for discussion and information sharing and a platform for strategic planning and project identification. It was in this context that I was invited to join the expedition to TL2. Without the expert leadership of the Arcus Great Ape Programme Director, Annette Lanjouw, a trip to a region as politically unstable and remote from my understanding as the Congo would have been impossible for me. Annette’s years of accumulated knowledge and experience in the Congo, with gorilla and bonobo conservation in particular, coupled with her diplomatic skills (she was the daughter of a Dutch ambassador) and natural charm has won her connections at all levels and enables her to negotiate the tricky political landscape of Central Africa.

Our trip has been meticulously planned and with immunization certificates, visas, schedules, information papers and back country equipment in hand, our small group meets up at the airport in Paris on Sept 1 for the 8 hour flight to Kinshasa, DRC’s capital. Arcus founder Jon Stryker, his partner Slo, Annette, my colleague John Fellowes and I make up the team. Stepping off the plane at our destination, passing through the airport and driving to our hotel, I become aware that I am entering a world entirely new to me. In fact, the first sign of this comes before landing, when I notice the pervasive haze of wood smoke – from fuel burning and forest clearance for agriculture – that extends even above the clouds. I have traveled throughout China, India and South East Asia, yet the sights, sounds and smells of Kinshasa find little to relate to in my inventory of experience. We stay in the Memling hotel, in the most upmarket part of town, yet our surroundings are run down and seem to bear little resemblance to any other major city that I have visited.

As with subsequent nights that I spend in central Kinshasa, my first is filled with strange, heavy dreams. I wonder, the next morning, how much of this might have to do with the suffering this city has seen and continues to bear witness to. Around 10 million people live, for the most part, in sprawling slums…

A little more history: following independence, there was a democratically elected leader, Lumumba, but he was overthrown almost immediately in a Belgian and US-backed coup; this led to the installation of the dictator, Mobutu, who renamed the country Zaire in 1971. Years of oppressive rule were brought to an end when he was expelled in 1997 by rebel forces led by Laurent Kabila. However, a resource war with neighbouring countries soon followed and the political and economic forecasts remain uncertain.

Still, in spite of the heaviness that I feel, my spirits are high: on our agenda that day is a visit to Lola Ya Bonobo, a bonobo sanctuary on the outskirts of the city, established by the incomparable Claudine André.

Bonobo – An Expedition Diary by Andrew McAulay (Part II)